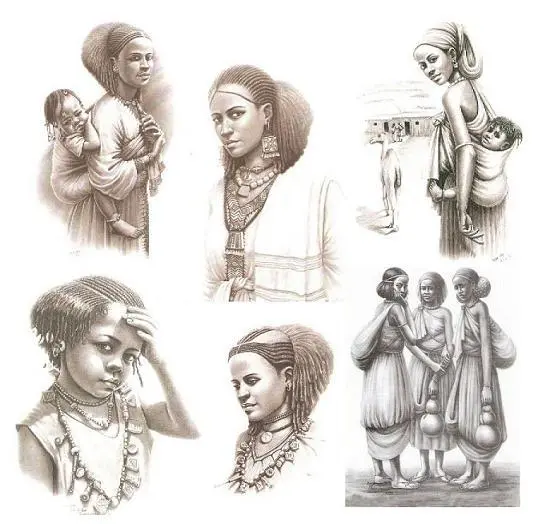

WOMEN OF POWER IN ETHIOPIAN LEGEND AND HISTORY

http://www.oneworldmagazine.org/focus/etiopia/women.html

by Rita Pankhurst

“Highly placed Ethiopian women, who combined worldliness, politics and religion are seen again and again in Ethiopian history. Rita Pankhurst recalls how women have been as important and influential as any man.”

Lucy, alias Dinknesh – literally “you are lovely” – is the first woman in Ethiopian history, indeed in the history of the world. She was a dainty little person, an intrepid walker who came down from the trees some three million years ago in the Afar region of eastern Ethiopia. An American – French team of physical anthropologists led by Donald C. Johanson found 40 per cent of her skeleton in 1974, and named her Lucy after the Beatles song – though her Ethiopian descendants prefer to call her Dinknesh. The extent of her influence or power will forever remain a mystery.Whereas Lucy’s fossilised bones are real nothing is known of her story. But when it comes to the Queen of Sheba there is a great story yet no concrete evidence to support it. Do not deny her existence in Ethiopia, however.

One eminent Ethiopian historian, who referred to her at a public lecture in Addis Ababa as a legendary figure, was soon in trouble with the indignant audience.

According to the Ethiopian national epic, Kabra Negast , compiled in the 14th century, Makeda, the Queen of Sheba, who visited King Solomon in the Old Testament times, came from Tigre in Northern Ethiopia. She made the arduous journey across the desert and the Red Sea with her retinue and rich gifts to learn wisdom from the great king. Later, he beguiled her into sleeping with him and on her return, she gave birth to a son, Menelik the First. According to legend he was the founder of the Ethiopian Solomonic dynasty, which supposedly ended only with the deposition of Emperor Haile Selassie in 1974.

In Ethiopia it was considered quite natural that a woman should have held supreme power. Here was a woman to whom courage and endurance were attributed, who had intellectual and spiritual interests, and was willing to endure hardship in search of knowledge.

Two thousand years later, probably in the 10th century AD another legendary queen took the stage in Ethiopia. Although something of the Aksumite Empire she overthrew is known, from the inscriptions and monuments left behind, and from observations of foreign traders, there little more authentic information about her than about Makeda. There is evidence only that a rebellious queen led the forces which destroyed the old Christian order. Variously referred to as Gudit, Gwedit, Yodit, Judith, and as “Isat” – Amharic for fire – she was believed to be the founder of the Zagwe dynasty which ruled for several hundred years.

Alleged by some to have followed an indigenous religion, and by others to have been of Jewish faith, she was, all agree, a fearsome warrior who led her troops to victory over the Christian Aksumites. Whether real or legendary, she remains an impressive example of a woman military leader who wielded power.

“In the later years of the Zagwe dynasty, towards the end of the twelfth and the beginning of the thirteenth century, when Ethiopian rulers were once again Christian, there lived a woman of a different disposition from Gudit, the devout and beloved wife of the venerable King Lalibela, who created the world-famous complex of rock-hewn churches that bear his name.”

Masqal-Kebra, literally “Glory of the Cross”, was a strong and influential consort who succeeded in persuading the head of the Ethiopian Church to ordain her brother as bishop – and is said to have persuaded the King to abdicate in favour of his nephew. But, when she discovered the nephew had mistreated a poor farmer, she advised her husband to take the throne back.Known for her piety she is said to have built the Abba Libanos Church at Lalibela, in honour of her husband. In Lasta, the country around Lalibela where she was born, and in Tigre, where a monastery is named after her she was indeed, deeply revered. Indeed, Masqal-Kebra is numbered among the Ethiopian saints and two unpublished manuscripts of her life are preserved, one at Gannata Maryam Church near Lalibela, the other at Aksum.

Masqal-Kebra was typical of highly-placed Ethiopian women, who combined worldliness and other-worldliness, politics and religion, in a mix which is seen again and again in Ethiopian history.

Some three centuries later a Muslim princess from Hadya, in south-western Ethiopia, was given in marriage to the future Emperor Baeda Maryam to cement an alliance with her motherland. However, she was far from being simply a chattel in a dynastic arrangement. During the ten years of her husband’s reign (1468-1478) Empress Eleni became well-versed in Christian theology.

She even wrote two religious works, one concerning the laws of God, and the other, the Holy Trinity and the purity of St. Mary.

In daily life she was pious and kind, and took an interest in the welfare of other people. Her character made her so widely respected that, far from retiring after her husband’s death, she continued to exert political influence during the following three reigns.

She played a decisive role in choosing her grandson, Lebna Dengel, as Emperor. As he was then a minor, she served as one of the regents till he came of age. During her regency many churches were repaired and many more built. She also sponsored the translation of Greek and Arabic religious texts in Ge’ez, the language of the Ethiopian Orthodox Church.

Because of her political experience and skill, Eleni became the most important of the regents. She foresaw the menace of Turkish aggression at the coast and the need for allies to fend off the growing power of the vassal Muslim states threatening the Christian Empire’s vital trade routes to the sea.

When Dom Manuel, King of Portugal, sent envoys seeking an alliance against Egypt and other Muslim powers in the Indian Ocean, Eleni welcomed these envoys, and sent an ambassador to Portugal with a letter suggesting joint action in defence of Christianity. Eventually however, when a second Portuguese mission landed in response to her overtures in 1520, Lebna Dengel had assumed the reins of power. Lacking the wisdom of his grandmother, he failed to grasp the importance of the alliance, a misjudgment which cost him dearly in later years. On the plus side, the chaplain to that mission, Francisco Alvares, left for posterity a detailed account of the Ethiopian court and the part of the country visited by the mission.

Eleni continued to exert a moderating influence on the impetuous young monarch until her death in 1522. The fact that Eleni was a woman was no bar to her exerting influence at court and wielding great power, in diplomatic as well as domestic affairs of state. Nor did it prevent her making a significant contribution to the Ethiopian Church.

” After Eleni’s death Emperor Lebna Dengel’s own wife, Sabla Wangel, began to assume as significant a role in Ethiopian history as Eleni’s had been. This was the time when Imam Ahmad ibn Ibrahim, nicknamed “Gragn” – the left-handed – led a revolt from his birthplace in the Emirates of Adal, in the lowlands towards the southern entrance to the Red Sea.”

At times with the help of Turkish musketeers, he conquered more and more of the Christian highland state, so that the royal family had constantly to be on the move. Sabla Wangel’s eldest son was killed in battle and her fourth son, Minas, was taken prisoner, saved from execution by Ahmed’s wife, Del Wambara. Sabla Wangel shared in her husband’s attempts to stem the Adal tide until he was forced to find refuge on the impregnable top of Mount Dabra Damo, where he died in 1540.Sable Wangel’s second son, Galawdewos, then came to the throne and the war continued. While he was fighting in the south of the country a year later, the long-promised help from Portugal arrived. From the mountain fortress in the north, where she had remained after husband’s death, the Empress negotiated with the Portuguese before descending to their camp. She was met by their commander, Christovao da Gama, the son of the explorer Vasco da Gama. Seated on a mule she reviewed the contingent of 400 Portuguese troops who paraded in front of her.

Sabla Wangel’s presence rallied support for the Portuguese whom she advised, encouraging local farmers to supply them with provisions. Many joined the Portuguese to drive out the invader, whose soldiers burnt many settlements and churches. She was present during a number of battles, tending the wounded, tearing her headgear and clothes to make bandages, and mourning the dead, among them the Portuguese commander himself. In 1543 the remnants of Christovao’s force helped Emperor Galawdewos defeat and kill Imam Ahmad. The latter’s wife, Bati Del Wambara, succeeded in escaping, but her son, Muhammad, was taken prisoner.

Sabla Wangel was then able to negotiate the exchange of her son Minas, for Ahmad’s son, plus a ransom in gold. Minas had been handed over to the Turkish Sultan, Suleiman the Magnificent, as a symbol of Adal vassalage. The exchange succeeded, despite doubts on both sides, thanks to the joint efforts of the two women, Sabla Wangel and Del Wambara.

Six years of continuous fighting later, Galawdewos was killed, after which his brother Minas came to the throne. During his four-year reign Sabla Wangel continued to be influential in court and religious affairs. In the controversy engendered by the Jesuits, who had entered the country during Galawdewos’s reign, and were aiming to bring Ethiopia into the Roman Catholic fold, she was a steadfast supporter of the traditionalists who wished Ethiopian Christians to remain Orthodox. But this did not prevent her from interceding on behalf of foreign Roman Catholics who had fallen foul of the Emperor. Her intervention saved from execution both the Portuguese adventurer Bermudes, who had angered Galawdewos, and the Spanish Jesuit Patriarch Oviedo, whom Minas had condemned. Her last achievement was to ensure that her grandson, Sartsa Dengel, one of several rival contendants, came to the throne. Her choice was a wise one as he succeeded in defending the integrity of the realm throughout his thirty-four year reign.

Sabla Wangel conformed to the model of wise Ethiopian queens who were deeply involved in affairs of state, while retaining the qualities of gentleness and mercy often attributed to women. It fell to her to live in dangerous times, which required not only diplomatic talents, but also courage and fortitude in battle and defeat. Many women refugees today would have particular sympathy for her sufferings and endurance.

Del Wanbara – literally “Victory is her seat” – held the title of Bati. A contemporary of Sabla Wangel’s, she was the daughter of Imam Mehefuz, governor of Zayla, a port on the Gulf of Aden close to what is now Djibouti. He was also the de facto ruler of the state of Adal. She married Imam Ahmad and, ignoring the protests of his soldiers, accompanied him on his expeditions of conquest in the Christian highlands. At times she had to be carried on their shoulders up and down steep and rocky mountain slopes, twice in a state of pregnancy. She gave birth to two sons – Muhammad in 1531 and Ahmad two years later – during campaigns in the mountains of Tigre.

After the defeat and death of her husband in 1543 and the capture of her young son Muhammad, she fled to the north-west of Lake Tana, and eventually succeeded in returning to Harar, then at the centre of Adal power. Her first task was to make arrangements for the exchange of her eldest son Muhammad for Emperor Galawdewo’s brother, Minas. She was in a good position to achieve this ambition because Minas’s life had been spared through her intervention. It was no easy task, however, as his captors feared, rightly as it turned out, that if released, he might come to the throne, and be a powerful enemy. Del Wanbara was determined to avenge her husband’s death and, nine years later, agreed to marry the Emir of Harar, Nur Ibn Mujahid, son of her first husband’s sister, seeing in him the best prospect of achieving her aim. Emir Nur began by rebuilding Harar, which had been sacked, and enclosed the town with a wall which can be seen to this day. Having reorganised his forces, he undertook a new conquest of the Christian highlands and, in 1559, killed Emperor Galawdewos in battle, thus fulfilling Del Wanbara’s wish to avenge the death of her first husband.

Del Wanbara and Sabla Wangel were in some ways mirror images of each other. Both were strong wives closely involved in their husbands’ battles: Sabla Wangel in defending the Christian highland state, Del Wanbara in supporting the attack on it by a Muslim army. Both lost their husbands in the struggle, and knew what it meant to be a fugitive. Both suffered the agony of seeing one of their sons taken into captivity. Both fought with all their might for their sons’ release, and had enough influence to achieve it. Thus both were examples of women of immense strength of character, able to fight for their own kin, but also women whose actions inspired their followers and helped change the course of history.

“By contrast, the great 18th-century Empress Berhan Mugasa, better known as Mentewab – literally “how beautiful you are” – lived in quieter times. According to legend, while wandering about his domain in the disguise of a poor man, as was his habit, Emperor Bakaffa fell ill of a fever in a poor village in the district of Quara, west of Lake Tana. “

A respectable old man, who lived on a hill above the unhealthy plain, took pity on the stranger and had him carried to his house. His beautiful daughter nursed the stranger gently back to health, with foreseeable consequences. Bakaffa fell in love and found that she was of noble family. She was brought to his palace at Gondar, the capital, where she bore him a son. To secure her position at court and ensure that her son succeeded to the throne, she adroitly gathered around her a devoted group of relatives so that, when her husband died in 1730, there was no difficulty in her young son being proclaimed Emperor Iyasu II, and herself being crowned Empress two months later. With the backing of her relations whom she had promoted to positions of power, she remained regent for more than 30 years.There was only one serious challenge to her rule during the quarter century of Iyassu’s reign. Two years after his accession a group of noblemen not from her clan conspired against her. They surrounded her and her son in their castle at Gondar, the capital, but Mentewab held out for two weeks until they were rescued. She arranged for her son to marry the daughter of an Oromo chief, and through his alliance many Oromos gradually gained influence at court.

Enlightened and liberal-minded, Mente-wab succeeded in reconciling the followers of the two major monastic orders, who had for centuries engaged in bitter disputes over church doctrine. She was also a great patron of the arts and literature, financing the building of many fine churches and stimulating the production of richly illuminated manuscripts and paintings.

Her little palace at Gondar was the most elegant of any within the enclosure of palaces at the capital, and she protected the Greek and Syrian artisans employed on palace building. After the death of her son in 1755, her grandson Iyoas came to the throne and she continued to serve as regent.

She later made her home at Qusquam, on the outskirts of the capital, where she had earlier built a splendidly decorated palace and richly endowed church.

The Scottish explorer, James Bruce, who was in Gondar in 1770 and 1771, considered – her his friend and benefactor, describing her as “bountiful and unfailing in good deeds, intensely kind and charitable, extremely devout”. He observed that, though she had never been there, she was “perfectly well acquainted” with Jerusalem, the Holy Sepulchre, Calvary, the City of David and the Mount of Olives.

In her last years Mentewab’s power waned, so that she could do little more than witness the disintegration of the empire and the decline in the fortunes of her family. However, she still retained some vestiges of her former status. Bruce noted that she was seated with her grandson at state banquets only two or three years before her death in 1773.

While carrying on the Ethiopian tradition of highly devout queens wielding great political power, Mentewab introduced a new element of elegance and artistic refinement which distinguished her from both her predecessors and her successors.

One of these successors, Taytu Betul, married King Menelik II and was crowned Queen of Shewa in 1883, little more than a century after Mentewab’s death.

Born near Gondar of a princely family partly of Oromo descent, she had already been married several times before the age of 30, but had no children. Enduring the ups and downs in the political fortunes which befell her previous husbands, she was already experienced in the workings of the Ethiopian power structure before she became Menelik’s wife. In 1889, two days after Menelik’s coronation as Emperor, Taytu, which in Amharic means “the Sun”, was crowned Empress. Thereafter, her official title became “Light of Ethiopia”, and these words appeared on her seal.

Taytu acquired the accomplishments that befitted her rank. But she was more educated than the average lady of her day and could read and write Amharic. As her stepfather had administered the monastery at Debre Mewi in Gojam, she had the opportunity to live near a religious community and it is no doubt there that she learned Ge’ez. She was conversant with Christian Orthodox doctrine, composed religious poetry in Ge’ez, could play the begena, a royal lyre supposedly descended from the biblical King David’s harp, and was adept at Ethiopian chess, a form of the game closely related to that played in the Middle East in medieval times. It was Taytu who encouraged the Emperor to move the capital from the storm-swept heights of Entoto to the lower altitude and more pleasant climate around the hot springs of Finfine.

A strong-minded woman, Taytu remained a close adviser to her husband throughout his reign. She provided a counter-balance to Menelik who, she considered, was too trusting of the various foreigners intriguing at his court, and too eager to accept the innovations they wished to introduce.

In 1890, in the era of colonialist expansion, there was a dispute between Italy and Ethiopia over the Treaty of Wechale between the two countries. The Amharic text stated that Menelik could avail himself of Italy’s good offices in dealing with European powers, whereas the Italian text made it mandatory for him to do so.

On the basis of the Italian text, Italy claimed to have established a protectorate over all Ethiopia. Menelik refused to accept this claim.

In Taytu’s presence, the Italian envoy, Count Antoneli, is quoted as having said to Menelik: “Italy cannot notify the other powers that she was mistaken . . . because she must maintain her dignity.”

At this point Taytu intervened, saying: “We also have our dignity to preserve. You wish Ethiopia to be represented before other powers as your protectorate, but this shall never be. ”

In 1896, when it became clear that the Italians could not longer be kept at bay, and Menelik decided to confront them, Taytu was vindicated in her hostility to foreign powers. She took part in the war of 1895-96 against the Italians, and brought 3,000 of her own troops to Adwa, to join those of leaders from various parts of the Empire.

Internal rivalries were buried in a supreme effort to defend the country. The ensuing Ethiopian victory, exactly 100 years ago, was an event of major importance in African history, and brought about the downfall of the Italian Government.

Taytu was a great businesswoman, generous to her friends but ruthless to her enemies. She managed her vast estates with acumen and directed the huge organization required to feed and provide drink for thousands of soldiers and officers of state at the lavish banquets which Menelik gave several times a week in the great banqueting hall of the Addis Ababa palace.

Thousands worked daily to grind the grain into flour and prepare the honey wine, which was piped into barrels before being served in narrow-necked glass globes.

Among Taytu’s ventures was Addis Ababa’s first important hotel, which bore her title, Eteghe. Under the name of Taytu Hotel, it still stands today, a memorial to her enterprise and to the picturesque architecture which distinguished the Addis Ababa of her time.

During the last few years of Menelik’s reign, as his health gradually deteriorated, Taytu became in practice the ruler of Ethiopia. Having no children of her own, she attempted, in the traditional way, to build up an alternative power base by promoting her relatives and by dynastic marriages. In this she failed, and in 1910 the then newly established Council of Ministers banished her from their meetings to Menelik’s sickroom. From that moment her influence declined, and in 1913, as soon as he had died, she was escorted with a small retinue up the very hills of Entoto from which the capital had been moved at her bidding. There, dressed simply, she spent her last five years in prayer and fasting, as she was refused permission to return to her native Gondar.

Like earlier Ethiopian queens, Taytu was a prominent figure in the affairs of state of her time. She knew, as they did, the meaning and intoxication of power. She was not renowned for a sweet disposition, but there is no doubt that she added to the evidence that there have been women in Ethiopian history as important and influential as any man.

batti del wambara is a somali and so is Ahmed Gurey/gragn

kid

July 26, 2010 at 12:54 pm

The Tree of Life

The Bible tells us that God instructed Noah to build his ark from “gofer wood” — another name for the Cypress tree. (Revelations 1:11 and 2:18) Noah is a good starting point for our story because it is Noah’s son, Shem, whose descendants gave way to the Queen of Sheba and the founding of Yemen’s capitol, Sana’a. The Queen’s empire was wealthy and firmly established in the South Arabian peninsula until she unexpectedly moved her kingdom across the Red Sea to Ethiopia.

The Cypress tree was known in Ethiopia as Thyia, after the Ethiopian region of Thyia where it was cultivated in groves, and where the descendants of the Queen lived. The Queen and her offspring were generally considered to be “jinn” — a type of magical or superhuman from whence we get the term “genie.” One characteristic that identified the “jinn” was a complexion of light skin which stood in marked contrast to the dark skin of Arabic, African and Semitic people of the region. A descendent of the Queen, Lady Rodophos Nitrocris, daughter of Ethiopian King Phiy, was such a “jinn.” In fact, the term “ruddy complexion” comes from Lady Rodophos first name. In earlier times, this Rodophos or “ruddy” complexion was sufficient reason to be put death by fearful rulers. Lady Rodophos would, along with the Thyia tree, become the guardian of human civilization.

As John McGovern told us the story, we began to understand how fragile and incomplete our traditional history of this era was.

In the seventh century before Christ, the Assyrians under King Ashurbanipal, were marching West towards Egypt, laying waste to the nations that were in their path. Prior to his arrival in Egypt, that empire had joined with Ethiopia to form a stronghold against the invading Assyrians. The 26th dynasty of Egypt, also called the “Ethiopian dynasty” was ruled by Ethiopian King Phiy. Realizing the dangers that were ahead, Lady Rodophos formed a brotherhood of Kings, called Adelphos, and sought to move the cultural centers from Africa and Asia to new and more secure locations in South Europe. Her plan would establish libraries, schools and oracle sanctuaries that would insure against the demolition of the Assyrians.

To perform this urgent preservation of knowledge and scholarship, King Phiy needed a capable leader who could be trusted with this important task, and he found such a leader in Lady Rodophos’ brother, Taharka Aesiopis. Taharka was a black man from Ethiopia, a descendent of Noah, and more famous for his metaphorical stories (i.e. Aesop’s fables) than his true contribution to Western Civilization.

Lady Rodophos became Egypt’s “Divine Votaris,” the symbolic wife of the god Amon and the functional High Priestess of Africa, Asia and Europe. Her exact title was Thyia, “the Sacred Mother of the Thyia trees.” She was also known as Athena Nikephoros, goddess of ‘wisdom’ and the famous “black Athena” — goddess of wisdom and victory. Although her complexion was light, she was racially Ethiopian.

As each new center of knowledge was transplanted to safer locations, a small army of workers preceded the armada and prepared the land by planting a sacred grove of Thyia trees. So important and essential was this particular tree that an entire oracle center was once moved hundreds of kilometers because the Thyia grove was no longer viable. We know that the resin from this tree was used in the sacred fires that smoked beneath the oracle’s seat, where they were usually suspended on an elevated tripod. We know that many sacred objects were constructed using the wood of this tree. But the exact significance of the tree remains elusive.

The Thyia (Callitrus) tree is a Gondwana Flora and therefore native to the Southern hemisphere; e.g. Australia, Africa, India and South America. The Thyia trees was also taken to Malta and Morocco where it is known by it’s Phoenician name, the Arar tree. The name means leathery skin, referring to the it’s amazing ability to heal flesh wounds and Thyion resin varnish’s tough protective skin. Thyia was transplanted to Greece by Taharka/Aesop and Nitocris/Thyia and their ‘Boat People’.

The Thyia tree was sacred to the Zoroastrians God of Light Ormazd. His worshipers had taken the tree to Armenia in prehistoric times as attested to by petroglyphs from Armenia, clearly showing the Thyia ‘Tree of Life’ growing out of the body of the cosmic Serpent. (This is a metaphor for it’s ability to commune between Earth-cosmic Serpent and the stellar-cosmic serpent formed by the galactic arm in the southern skies, as an antenna to the gods). From Armenia, the tree was taken into western China where Thyia bestowed her manifold gifts.

taufik adms

October 11, 2010 at 11:15 am

@taufik adms you’re confusing sudan (kush) with axum (kush/sheba) because there’s no such tree in ethiopia. also pharaoh taharqa ruled modern day sudan not axum/sheba.

Trees of Ethiopia

en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Category:Trees_of_Ethiopia

Kevin

January 27, 2016 at 12:56 am