Posts Tagged ‘Deir Sultan’

Deir Sultan, Ethiopia and the Black World

By Negussay Ayele

Background to Deir Sultan at a glance

Unknown by much of the world, monks and nuns of the Ethiopian Orthodox Church, have for centuries quietly maintained the only presence by black people in one of Christianity’s holiest sites—the Church of the Holy Sepulcher of Jesus Christ in Jerusalem. Through the vagaries and vicissitudes of millennial history and landlord changes in Jerusalem and the Middle East region, Ethiopian monks have retained their monastic convent in what has come to be known as Deir Sultan or the Monastery of the Sultan for more than a thousand years. Likewise, others that have their respective presences in the area at different periods, include Armenian, Russian, Syrian, Egyptian and Greek Orthodox/Coptic Churches as well as the Holy See. As one writer put it recently, “For more than 1500 years, the Church of Ethiopia survived in Jerusalem. Its survival has not, in the last resort, been dependent on politics, but on the faith of individual monks that we should look for the vindication of the Church’s presence in Jerusalem….They are attracted in Jerusalem not by a hope for material gain or comfort, but by faith.” It is hoped that public discussion on this all-important subject will be joined by individuals and groups from all over the world, particularly the African Diaspora. At this time, I will confine myself to offering a brief profile of the Ethiopian presence in Jerusalem and its current state of turmoil. I hope that others with more detailed and/or first hand knowledge about the subject will join in the discussion.

Accounts of Ethiopian presence in Jerusalem invoke the Bible to establish the origin of Ethiopian presence in Jerusalem. Accordingly, some Ethiopians refer to the story of the encounter in Jerusalem between Queen of Sheba–believed to have been a ruler in Ethiopia and environs–and King Solomon, cited, for instance, in I Kings 10: 1-13. According to this version, Ethiopia’s presence in the region was already established about 1000 B.C. possibly through land grant to the visiting Queen, and that later transformation into Ethiopian Orthodox Christian monastery is an extension of that same property. Others refer to the New Testament account of Acts 8: 26-40 which relates the conversion to Christianity of the envoy of Ethiopia’s Queen Candace (Hendeke) to Jerusalem in the first century A.D., thereby signaling the early phase of Ethiopia’s adoption of Christianity. This event may have led to the probable establishment of a center of worship in Jerusalem for Ethiopian pilgrims, priests, monks and nuns.

Keeping these renditions as a backdrop, what can be said for certain is the following. Ethiopian monastic activities in Jerusalem were observed and reported by contemporary residents and sojourners during the early years of the Christian era. By the time of the Muslim conquest of Jerusalem and the region (634-644 A.D.) khalif Omar is said to have confirmed Ethiopian physical presence in Jerusalem’s Christian holy places, including the Church of St. Helena which encompasses the Holy Sepulcher of the Lord Jesus Christ. His firman or directive of 636 declared that“the Iberian and Abyssinian communities remain there” while also recognizing the rights of other Christian communities to make pilgrimages in the Christian holy places of Jerusalem. Because Jerusalem and the region around it, has been subjected to frequent invasions and changing landlords, stakes in the holy places were often part of the political whims of respective powers that be. Subsequently, upon their conquest of Jerusalem in 1099, the Crusaders, had kicked out Orthodox/Coptic monks from the monasteries and installed Augustine monks instead. However, when in 1187 Salaheddin wrested Jerusalem from the Crusaders, he restored the presence of the Ethiopian and other Orthodox/Coptic monks in the holy places. When political powers were not playing havoc with their claims to the holy places, the different Christian sects would often carry on their own internecine conflicts among themselves, at times with violent results.

|

Contemporary records and reports indicate that the Ethiopian presence in the holy places in Jerusalem was rather much more substantial throughout much of the period up to the 18th and 19th centuries. For example, an Italian pilgrim, Barbore Morsini, is cited as having written in 1614 that “the Chapels of St. Mary of Golgotha and of St. Paul…the grotto of David on Mount Sion and an altar at Bethelheim…”among others were in the possession of the Ethiopians. From the 16th to the middle of the 19thcenturies, virtually the whole of the Middle East was under the suzerainty of the Ottoman Empire. When one of the Zagwe kings in Ethiopia, King Lalibela (1190-1225), had trouble maintaining unhampered contacts with the monks in Jerusalem, he decided to build a new Jerusalem in his land. In the process he left behind one of the true architectural wonders known as the Rock-hewn Churches of Lalibela. The Ottomans also controlled Egypt and much of the Red Sea littoral and thereby circumscribed Christian Ethiopia’s communication with the outside world, including Jerusalem. Besides, they had also tried but failed to subdue Ethiopia altogether. Though Ethiopia’s independent existence was continuously under duress not only from the Ottomans but also their colonial surrogate, Egypt as well as from the dervishes in the Sudan, the Ethiopian monastery somehow survived during this period. Whenever they could, Ethiopian rulers and other personages as well as church establishments sent subsidies and even bought plots of land where in time churches and residential buildings for Ethiopian pilgrims were built in and around Jerusalem. Church leaders in Jerusalem often represented the Ethiopian Orthodox Church in ecumenical councils and meetings in Florence and other fora.

During the 16th and 17th centuries the Ottoman rulers of the region including Palestine and, of course, Jerusalem, tried to stabilize the continuing clamor and bickering among the Christian sects claiming sites in the Christian holy places. To that effect, Ottoman rulers including Sultan Selim I (1512-1520) and Suleiman “the Magnificent” (1520-1566) as well as later ones in the 19th century, issued edicts or firmans regulating and detailing by name which group of monks would be housed where and the protocol governing their respective religious ceremonies. These edicts are called firmans of the Status Quo for all Christian claimants in Jerusalem’s holy places including the Church of the Holy Sepulcher which came to be called Deir Sultan or the monastery (place) of the Sultan. Ethiopians referred to it endearingly as Debre Sultan. Most observers of the scene in the latter part of the 19th Century as well as honest spokesmen for some of the sects attest to the fact that from time immemorial the Ethiopian monks had pride of place in the Church of the Holy Sepulcher (Deir Sultan). Despite their meager existence and pressures from fellow monks from other countries, the Ethiopian monks survived through the difficult periods their country was going through such as the period of feudal autarchy (1769-1855). Still, in every document or reference since the opening of the Christian era, Ethiopia and Ethiopian monks have been mentioned in connection with Christian holy places in Jerusalem, by all alternating landlords and powers that be in the region.

As surrogates of the weakening Ottomans, the Egyptians were temporarily in control of Jerusalem (1831-1840). It was at this time, in 1838, that a plague is said to have occurred in the holy places which in some mysterious ways of Byzantine proportions, claimed the lives of allEthiopian monks. The Ethiopians at this time were ensconced in a chapel of the Church of the Holy Sepulcher (Deir Sultan) as well as in other locales nearby. Immediately thereafter, the Egyptian authorities gave the keys of the Church to the Egyptian Coptic monks. The Egyptian ruler, Ibrahim Pasha, then ordered that all thousands of very precious Ethiopian holy books and documents, including historical and ecclesiastical materials related to property deeds and rights, be burned—alleging conveniently that the plague was spawned by the Ethiopian parchments. Monasteries are traditionally important hubs of learning and, given its location and its opportunity for interaction with the wider family of Christiandom, the Ethiopian monastery in Jerusalem was even more so than others. That is how Ethiopians lost their choice possession in Deir Sultan. By the time other monks arrived in Jerusalem, the Copts claimed their squatter’s rights, the new Ethiopian arrivals were eventually pushed off onto the open rooftop of the church, thanks largely to the machinations of the Egyptian Coptic church.

Although efforts on behalf of Ethiopian monks in Jerusalem started in mid-19th Century with Ras Ali and Dejach Wube, it was the rise of Emperor Tewodros in 1855 in Ethiopia that put the Jerusalem monastery issue back onto international focus. When Ethiopian monks numbering a hundred or so congregated in Jerusalem at the time, the Armenians had assumed superiority in the holy places. The Anglican bishop in Jerusalem then, Bishop Samuel Gobat witnessed the unholy attitude and behavior of the Armenians and the Copts towards their fellow Christian Ethiopians who were trying to reclaim their rights to the holy places in Jerusalem. He wrote that the Ethiopian monks, nuns and pilgrims “were both intelligent and respectable, yet they were treated like slaves, or rather like beasts by the Copts and the Armenians combined…(the Ethiopians) could never enter their own chapel but when it pleased the Armenians to open it. …On one occasion, they could not get their chapel opened to perform funeral service for one of their members. The key to their convent being in the hands of their oppressors, they were locked up in their convent in the evening until it pleased their Coptic jailer to open it in the morning, so that in any severe attacks of illness, which are frequent there, they had no means of going out to call a physician.’’ It was awareness of such indignities suffered by Ethiopian monks in Jerusalem that is said to have impelled Emperor Tewodros to have visions of clearing the path between his domain and Jerusalem from Turkish/Egyptian control, and establishing something more than monastic presence there. In the event, one of the issues which contributed to the clash with British colonialists that consumed his life 1868, was the quest for adequate protection of the Ethiopian monks and their monastery in Jerusalem.

Emperor Yohannes IV (1872-1889), the priestly warrior king, used his relatively cordial relations with the British who were holding sway in the region then, to make representations on behalf of the Ethiopian monastery in Jerusalem. He carried on regular pen-pal communications with the monks even before he became Emperor. He sent them money, he counseled them and he always asked them to pray for him and the country, saying, “For the prayers of the righteous help and serve in all matters. By the prayers of the righteous a country is saved.” He used some war booty from his battles with Ottomans and their Egyptian surrogates, to buy land and started to build a church in Jerusalem. As he died fighting Sudanese/Dervish expansionists in 1889, his successor, Emperor Menelik completed the construction of the Church named Debre Gennet located on what was called “Ethiopian Street.” During this period more monasteries, churches and residences were also built Empresses Tayitu, Zewditu, Menen as well as by several other personages including Afe Negus Nessibu, Dejazmach Balcha, Woizeros Amarech Walelu, Beyenech Gebru, Altayeworq. As of the end of the 19th and the beginning of the 20th Century the numbers of Ethiopian monks and nuns increased and so did overall Ethiopian pilgimage and presence in Jerusalem. In 1903, Emperor Menelikput $200, 000 thalers in a (Credileone?) Bank in the region and ordained that interests from that savings be used exclusively as subsidy for the sustenance of the Ethiopian monks and nuns and the upkeep of Deir Sultan. Emperor Menelik’s 6-point edict also ordained that no one be allowed to draw from the capital in whole or in part. Land was also purchased at various localities and a number of personalities including Empress Tayitu, and later Empress Menen, built churches there. British authorities supported a study on the history of the issue since at least the time of kalifa (Calif) Omar ((636) and correspondences and firmans and reaffirmations of Ethiopian rights in 1852, in an effort to resolve the chronic problems of conflicting claims to the holy sites in Jerusalm. The 1925 study concluded that ”the Abyssinian (Ethiopian ) community in Palestine ought to be considered the only possessor of the convent Deir Es Sultan at Jerusalem with the Chapels which are there and the free and exclusive use of the doors which give entrance to the convent, the free use of the keys being understood.”

Until the Fascist invasion of Ethiopia in the 1930’s when Mussolini confiscated Ethiopian accounts and possessions everywhere, including in Jerusalem, the Ethiopian presence in Jerusalem had shown some semblance of stability and security, despite continuing intrigues by Copts, Armenians and their overlords in the region. This was a most difficult and trying time for the Ethiopian monks in Jerusalem who were confronted with a situation never experienced in the country’s history, namely its occupation by a foreign power. And, just like some of their compatriots including Church leaders at home, some paid allegiance to the Fascist rulers albeit for the brief (1936-1941) interregnum. Emperor Haile Sellassie was also a notable patron of the monastery cause, and the only monarch to have made several trips to Jerusalem, including en route to his self-exile to London in May, 1936. Since at least the 1950s there was an Ethiopian Association for Jerusalem in Addis Ababa which coordinated annual Easter pilgrimages to Jerusalem. Hundreds of Ethiopians and other persons from Ethiopia and the Diaspora took advantage of its good offices to go there for absolution, supplication or felicitation, and the practice continues today. Against all odds, historical, ecclesiastical and cultural bonding between Ethiopia and Jerusalem waxed over the years. The Ethiopian presence expanded beyond Deir Sultan including also numerous Ethiopian Churches, chapels, convents and properties. This condition required that the Patriarchate of the Ethiopian Orthodox Church designate Jerusalem as a major diocese to be administered under its own Archbishop.

Contemporary developments related to Deir Sultan

The foregoing pages should give the reader some idea of the deeply rooted but checkered and sinewy Ethiopian tenure in Jerusalem’s Deir Sultan. That the Ethiopian monastery has survived so far against all odds, is nothing short of a miracle. The different powers played havoc with the Ethiopian monks and nuns in Deir Sultan, taking away their key to their own chapel, changing locks on them, burning their precious religious materials, beating and mistreating them and eventually pushing them out of their central holdings in the main chapel of the Church of the Holy Sepulcher onto the rooftop of the Church. Still, they remained there making their own thatched roofs, linoleum ceiling covers, plants for shades, water well and makeshift cookeries and bathrooms. There they stayed fasting, praying, singing hymnals in the style of David of old. They also carried on their religious rituals and ceremonies in accordance with the practices and requisites of the Ethiopian Orthodox Church. Throughout its history the Ethiopian monastery has been a political football for Egyptian Copts and Armenian Orthodox in particular and the Turks and other overlords of the region in general. Most of the time, the Ethiopian state, was not in a position to do much on behalf of the Deir Sultan Ethiopian monks, as it was itself struggling for its survival and sovereignty in a hostile environment. Only towards the end of the 19thCentury, did the Ethiopian state and the Metropolitan in Addis Ababa start making some difference in stabilizing whatever could be salvaged from centuries of Egyptian/Coptic usurpation sustained by the Ethiopian monastery.

Egyptian government/Coptic cabal against Ethiopian/black presence in Jerusalem became even more politicized and more pronounced after the 1950’s when the Ethiopian Orthodox Church opted to be autocephalous, thereby ending the centuries old tutelage of the Alexandrian Coptic Church, which had until then provided the Metropolitan or Patriarch for the Ethiopian Church. The Egyptian Copts never got over that act of self-determination by the Ethiopian Church, and they were quick to peg their petty or greedy quest for complete takeover of all Ethiopian properties and possessions in the holy places, especially the prized Church of the Holy Sepulcher. To that end, they have leaned on the Egyptian government to pressure different landlords of Jerusalem including the Jordanians until 1967 and the Israelis since then. In one form or another, therefore, the question of Deir Sultan has become intertwined with the larger issue of Arab/Palestinian an Israeli conflict in the region. Technically, the Status Quo firmans issued in earlier times, as adumbrated in foregoing pages, are supposed to govern possessions of the holy places in question and relations among the Christian claimants of same. These firmans are not only rigorous and stringent, but it is also incumbent on all landlords that be–such as Turks, British, Jordanian or Israeli—to enforce them strictly to the letter. A recent report points out, for example, that the Status Quo“prohibits simple renovations, removal of fallen debris from the decaying ceiling, even sweeping has to be done in the dark or the Ethiopians risk being reported to the authorities by their Christian neighbors.” Despite such strict provisions, it is, as we have seen heretofore, the rights and footholds of the Ethiopian monks that have been continuously usurped, to benefit mainly the Egyptian Copts and then the Armenians and to some extent other groups as well. The Ethiopian monks are even victims of internecine rivalries and jockeying for advantages among the other Christian usual suspects.

When in 1948, the State of Israel came into existence in Palestine, Jerusalem was still part of the Kingdom of Jordan. The ever irksome Copts provoked a confrontation with Ethiopian monks in Deir Sultan which required Jordanian intervention or, more properly enforcement of the age-old Status Quo provisions. Given the somewhat frigid relations then between Egypt and Jordan on the one hand and the nascent cordiality between Emperor Haile Sellassie and King Hussein on the other at that moment, the Jordanian government ordered that the Egyptian Copts hand over the keys to Deir Sultan to the Ethiopians. When the Copts failed to comply with the order, the Jordanians went ahead and changed the locks and gave the new keys to the Ethiopians. This was, however, short lived as newfound courtship between Egyptian President Nasser and Jordanian king Hussein resulted in a Jordanian volte-face which reversed their earlier ruling and the keys were once again given to the Copts. As is well known, in its sweeping military victory over its Arab antagonists in the 1967 war, Israel occupied territories of Egypt, Syria and Jordan. More importantly, Israel wrested Jerusalem from Jordanian control and became henceforth the new landlord of the Christian holy places as well. And so, the problem of Deir Sultan was now squarely on Israel’s shoulders. And, it did not take long for their judgment to be tested. The chronic tug-of-war between the Copts and Ethiopian Orthodox monks flared up again in 1970, when the Israeli government is said to have changed the locks and given the keys to the Ethiopians. The Copts, as expected, did not take this lying down. They decided to take the matter to the Israeli courts where they filed papers alleging that they were the sole owners of Deir Sultan and that at best the Ethiopians were only guests with no property rights to the holy places. In 1971, the Israeli High Court is said to have ruled in favour of the Coptic claim and ordered that the government turn over the keys to the Copts. It is reported that the Israeli government did not comply with the court order insisting that “its dispute with the Copts was political and not legal and that the judiciary should desist from pressuring the government to resolve the case in court.” It is to be remembered that through all this, the Egyptian Copts have already usurped the main floor and chapel of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre and the Ethiopians are pushed to the rooftop of the Church. What the Copts want is for the Ethiopians to disappear once and for all from the scene, from the last vestige of presence they have maintained for nearly two thousand years altogether. With such Christian charity who needs enemies.

Despite the fact that the government of Emperor Haile Sellassie broke diplomatic relations with Israel in 1973, in solidarity with Egypt (an OAU member) which lost its Sinai territory, the Israeli government did not at this time retaliate by siding with the Egyptian Copts. To be sure, the Israelis were, and some say they still are, annoyed by Ethiopia’s decision which they regard as ‘betrayal’ and which also spawned an avalanche of diplomatic break off of ties with Israel by several other African countries, they did not retaliate on Deir Sultan for several reasons. One reason was that in the larger Arab-Israeli scheme of things, Deir Sultan does not figure big either for Egypt, the Arabs or for Israel. Sinai, the West Bank, the Golan Heights, Red Sea littoral and most importantly, sovereignty over Jerusalem as a whole and, when all is said and done, Palestinian/Arab and Israeli peaceful coexistence in the region are the most important issues. At best, the Deir Sultan issue is a nuisance to them as it has been for all landlords of Jerusalem historically.

Another reason for the Israeli reluctance to tackle the Deir Sultan dispute between mainly the Copts and the Ethiopian monks has to do with yet a different factor in the mix embedded in millennial history of the region. For a very long time, it was recognized by Zionist elements that several thousands of Ethiopians referred to in Ethiopia as falashas and now named bete Israelis as being more or less Jews and in the early 1970’s the rabbinical authorities had authenticated as Jews in exile from one of the lost tribes and therefore eligible for the right of return oraliyah to Israel. Thus, for several years Jewish groups in North America, Europe and Israel had been working painstakingly to safely facilitate the return of the Ethiopian Jews to Israel, and the Israeli government was well advised not to jeopardize this process by antagonizing the Ethiopian government(s) on the Deir Sultan issue. In the event, between the mid-1980’s and 1991 more than 60, 000 Ethiopian Jews have arrived in Israel.

It appears that the Egyptian government and the Copts have left no stone unturned to divest the Ethiopian Church of its rightful heritage in Jerusalem which is as much, if not more, legitimate as that of the Copts and other Christian sects. It is to be recalled that in 1978, then Israeli Prime Minister Menachem Begin and Egyptian president Anwar Sadat were negotiating land for peace through the good offices of U.S. president Jimmy Carter at Camp David. It is believed that in the course of those negotiations, Sadat privately raised the Deir Sultan issue on behalf of the Copts under his suzerainty, and it is intimated that Begin made some kind of personal promise to him. Inasmuch as what transpired or what exactly was promised was all personal, private and unregistered or not declared publicly at the time, one wonders if any responsible state or government would deem to be duty bound to act upon such informal exchanges. The Egyptians are said to have also raised the matter of Deir Sultan at the Israeli-Egyptian Normalization talks in 1986. What is of interest to us here in all of the above litany of Egyptian/Coptic pleas and goadings, is how relentless and dogged the Egyptians/Copts have been in their hostility to Ethiopian/black Christian presence in the Church of the Holy Sepulcher of Jerusalem.

This brings us to the latest physical clashes perpetrated by the Egyptian Coptic clerics in the Deir Sultan holy site in Jerusalem, which has been the subject of several reports by British, American, Israeli and Arab papers.

Unholy violence occurred in Christianity’s holiest place in Jerusalem at the end of July 2002, when an Egyptian Coptic priest, Father Abdel Malek, decided to bring a chair, go up to the rooftop of the Church, which is the last remaining preserve of the Ethiopian monks, and proceeded to sit there under the shade of a tree in clear violation of the Status Quo. It is to be remembered that, the cleric and his colleagues would not allow Ethiopians to visit, sit or worship in the Coptic chapels. The details are sketchy in terms who did what and when. However, it appears that when Ethiopians naturally tried to resist this wanton violation of their rights to their space by the impudent Copt, violent clashes erupted involving also Israeli policemen. In the melee, nearly a dozen monks, mostly Ethiopians suffered injuries and lascerations. After all that, it is reported that, escorted by Israeli police daily, Coptic cleric Abdel Malek continued to perch at the Ethiopian property, presumably until the Ministry of Religious Affairs issues a ruling on the matter. A question that comes on loudly to an interested observer is, “Why did the Copts choose this particular time to force a confrontation on Deir Sultan?” It seems that, given the volatile and bloody situation in Palestinian and Israeli relations, the Egyptians/Copts may have assumed that the Israelis may at the moment be ready to cave in and Deir Sultan’s rooftop may just be the kind of bone they can throw to them to elicit a possible or putative mediating role vis-à-vis the Palestinians. And the Egyptians/Copts continue to put pressure on Israel by inflaming Arab opinion. Egyptian President Mubarak is said to have boycotted an important regional meeting recently protesting the Deir Sultan affair. An Arab paper reported that earlier on, Pope Shenuda III of Alexandria lambasted Israeli Prime Minister Israel Sharon, calling on the Arab world to unite and put more effective pressure on Israel, inserting his pet agenda and saying, “the Israelis are occupying since 1970, the Deir Al Sultan church in east Jerusalem by force, and did not implement a ruling issued by the Jewish Supreme Court in favor of the (his Coptic) church.”

Since these shameful events, several deputations and representations to the Israeli authorities have been made by a newly formed “Ethiopian Association for Jerusalem” in the United States. These deputations took the form of written communications to the Israeli Embassy in Washington, D.C., and also in Tel Aviv and Jerusalem. Other concerned groups including the longstanding Association in Ethiopia and individuals of Ethiopian origin are, no doubt making efforts to let the authorities in Israel know their concern on the issue. It is also hoped that the black Jews from Ethiopia and elsewhere will also weigh in on the matter. Though the current regime in Addis Ababa is better known for its systematic destruction of Ethiopian history, culture, and integrity, it sent a delegation to Israel for perfunctory reasons and with no avail on behalf of the Ethiopian monks or the monastery. Given the split of the Ethiopian Orthodox Church in Addis Ababa and in the Diaspora, the Church’s effectiveness in successfully challenging the Egyptian Coptic pressures to eliminate Ethiopian, hence black presence in Jerusalem is a matter of serious concern.

Ethiopia and Black Heritage In Jerusalem

For hundreds of years, the name or concept of Ethiopia has been a beacon for black/African identity liberty and dignity throughout the Diaspora. The Biblical (Psalm 68:31) verse , “…Ethiopia shall soon stretch forth her hands unto God” has been universally taken to mean African people, black people at large, stretch out their hands to God (and only to God) in supplication, in felicitation or in absolution. As Daniel Thwaite put it, for the Black man Ethiopia was always “…an incarnation of African independence.” And today, Ethiopian monastic presence in the Church of the Holy Sepulcher or Deir Sultan in Jerusalem, is the only Black presence in the holiest place on earth for Christians. For much of its history, Ethiopian Christianity was largely hemmed in by alternating powers in the region. Likewise, Ethiopia used its own indigenous Ethiopic languages for liturgical and other purposes within its own territorial confines, instead of colonial or other lingua franca used in extended geographical spaces of the globe. For these and other reasons, Ethiopia was not able to communicate effectively with the wider Black world in the past. Given the fact that until recently, most of the Black world within Africa and in the Diaspora was also under colonial tutelage or under slavery, it was not easy to appreciate the significance of Ethiopian presence in Jerusalem. Consequently, even though Ethiopian/Black presence in Jerusalem has been maintained through untold sacrifices for centuries, the rest of the Black world outside of Ethiopia has not taken part in its blessings through pilgrimages to the holy sites and thereby develop concomitant bonding with the Ethiopian monastery in Jerusalem. Apropos to this theme, there is an initiative afoot by a few individuals to launch a “Forum for African Heritage in Jerusalem” website that can serve as a forum for education, dialogue and/or action by any and all concerned on Deir Sultan and the sustenance of Black presence there.

For nearly two millennia now, the Ethiopian Church and its adherent monks and priests have miraculously maintained custodianship of Deir Sultan, suffering through and surviving all the struggles we have glanced at in these pages. In fact, the survival of Ethiopian/Black presence in Christianity’s holy places in Jerusalem is matched only by the “Survival Ethiopian Independence” itself. Indeed, Ethiopian presence in Deir Sultan represents not just Ethiopian Orthodox Christianity but all African/black Christians of all denominations who value the sacred legacy that the holy places of Jerusalem represent for Christians everywhere. It represents also the affirmation of the fact that Jerusalem is the birthplace of Christianity, just as adherents of Judaism and Islam claim it also. The Ethiopian foothold at the rooftop of the Church of the Holy Sepulcher is the only form of Black presence in Christianity’s holy places of Jerusalem. It ought to be secure, hallowed and sanctified ground by and for all Black folks everywhere who value it. The saga of Deir Sultan also represents part of Ethiopian history and culture. And that too is part of African/black history and culture regardless of religious orientation.

When a few years ago, an Ethiopian monk was asked by a writer why he had come to Jerusalem to face all the daily vicissitudes and indignities, he answered, “because it is Jerusalem.” And the writer makes the perceptive observation that “The Ethiopian church in Jerusalem itself resembles a plant which in Jerusalem has found poor soil, but has continued to grow in defiance of the laws of probability and to survive the hardest winters and the hottest summers.” The number of Ethiopian monks and nuns domiciled in Deir Sultan today has shrank drastically from several hundreds at the turn of the century to a few dozens today. And they are of the view that “if they are forced to leave Deir as-Sultan Monastery, blacks will never again be represented in the sacred place.” It is hoped that henceforth not only Ethiopians but all other Black folks from every land in the African continent and in the Diaspora will embark on annual pilgrimages to the Ethiopian convent of Deir Sultan and assert their rights of representation in this holiest of holy Christian shrines in Jerusalem.

8 November 2002

Ethiopian Orthodox Church: History [short documentary]

“Three thousand years of history cannot not be wiped so easily”

An Ethiopian Easter in Jerusalem

Contrary to romantic perceptions, the streets of Jerusalem’s Old City by night are typically sinister and ghostly due to a combination of bad lighting and poor rubbish collection services, together with the cadres of patrolling Israeli police and soldiers armed with rifles and batons, and the scores of CCTV cameras that punctuate the walls of each winding alley.

But this weekend, the city’s streets took on a festive hue as thousands of orthodox pilgrims converged on the city’s Christian holy sites to celebrate the most important event in the Christian liturgical calendar: Easter.

One of the most lively and joyful of these celebrations is the Holy Saturday festival held at the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, which Christians believe to be built on the site of Jesus’ crucifixion, burial and resurrection.

The Holy Saturday festival commemorates the time that Jesus is said to have lain in the tomb and descended into hell, defying death and releasing those held captive there, including Adam and Eve.

According to orthodox tradition, at exactly 2pm on this day, a sun beam is said to shine on Jesus’ tomb, lighting 33 candles held by the Patriarch of the Greek Church who waits inside the tomb. The Patriarch then emerges carrying the Holy Fire to light the candles of thousands of worshippers that crowd into the Church for the ceremony.

But because of the strict guidelines defining which part of the Church belongs to which of the six churches based there, Jerusalem’s tiny Ethiopian community conducts its own Holy Fire ceremony later on Saturday evening in the courtyard of the Deir Al-Sultan monastery, which sits on the rooftop of the Church.

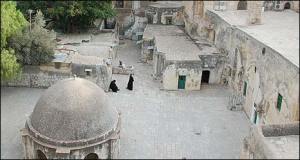

Deir Al-Sultan has been home to a community of Ethiopian monks since 1808. The monastery lies above the Chapel of the Finding of the Cross, where Queen Helena is believed to have discovered the three crosses used to crucify Jesus and the two thieves, Dismas and Gestas. It consists of several small chapels, including the Chapel of the Archangel Michael, and a courtyard with a dome in the centre which gives light to the Chapel of Saint Helena below.

During the Holy Saturday festival, the Archbishop of the Ethiopian Church, dressed in an elaborate golden garment, wearing a jewelled crown and sporting a candle carrying the Holy Fire, lights candles carried by monks, nuns and pilgrims wearing simple white cotton robes. Led by the Archbishop, the worshippers proceed to dance around the dome of the Chapel of Saint Helena to the sound of drums and to the smell of incense, chanting and singing as they go. The Archbishop then retreats to a tent erected outside the Chapel of the Archangel Michael especially for the occasion, where prayers continue.

The Ethiopian Holy Fire ceremony attracts a great deal of attention, and today the courtyard is filled with Israelis, Palestinians, Germans, Italians and a multitude of other nationalities vying for the best view of the festivities.

A spirit of joy prevails over the celebrations, fuelled by the infectious smiles of the Ethiopian pilgrims. While some of the younger worshippers pose with their candles for the many camera-toting media and tourists, some of the older members frown on, decidedly unimpressed by this outside attention.

Yet outside of the Easter festivities, the area is the site of a lengthy and sometimes violent turf war between the Ethiopian and Coptic churches, exacerbating and exacerbated by other disputes between the six churches competing for control over the Church: the Latins (Roman Catholics), Greek Orthodox, Armenian Orthodox, Syrian Orthodox, Copts, and Ethiopians.

Since its dedication around 335, the Church of the Holy Sepulchre has undergone many cycles of destruction and rebuilding often strongly linked to political upheavals that have persisted in the region throughout history. And since the accession to power of the Ottoman Turks in 1517, many political machinations among Christians trying to gain control over all or parts of the edifice have followed.

On Palm Sunday in 1767, a squabble broke out between the Greeks and Franciscans over rights to the Church. In order to put what they thought was a decisive end to the bickering, the Ottoman authorities passed a firman (imperial decree) splitting the Church and other holy sites in Palestine between the various Western and Eastern churches. This eventually came to be known as the Status Quo, basically a legal regime restating the different rights and powers enjoyed by the various Christian denominations over holy places in Jerusalem and Bethlehem, including the monastery of Deir Al-Sultan in Jerusalem.

Successive regimes promised to uphold the Status Quo throughout the 20th century, including the British, the Jordanian, and the Israelis. But neither the Jordanians nor the Israelis kept their Status Quo promises when it came to Deir Al-Sultan. In what some say was a jibe at the Egyptian authorities at the time, the Jordanians passed a ministerial decree in 1960 ordering the Coptic Church to hand over the monastery’s keys to the Ethiopians. When the Copts refused, the Jordanian police forcefully broke open the monastery’s locks and handed the new keys over to the Ethiopians. The Jordanian king personally intervened and ordered that the monastery be restored to the Coptic Church.

But the Jordanians lost East Jerusalem and the Old City when they were occupied by the Israelis in June 1967, and the dispute erupted yet again. On Coptic Easter in 1970, while the Copts were busy at midnight prayers in the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, Israeli police forcefully changed the locks at Deir Al-Sultan and handed over the monastery’s new keys to the Ethiopians. Despite a ruling by Israel’s High Court in 1971 that the monastery be returned to the Copts, no action was taken and the situation remains unresolved to this day.

For their part, the Ethiopians accuse the Copts of having taken over the monastery in 1838 when plague struck Jerusalem and all the Ethiopian monks died. According to the Ethiopians, the Copts burned down the library containing the documents which validated the Ethiopians’ claim to Deir Al-Sultan.

Today, a tense coexistence prevails between the Copts and the Ethiopians, one where even the most seemingly insignificant actions can spark off fierce internecine fighting. In 2002, an unholy brawl broke out when an Egyptian Coptic monk stationed on the roof decided to move his chair from its agreed spot into the shade. This was interpreted as a hostile move by the Ethiopians, violating an agreement that defines ownership over every nook and cranny in the Church. Rivals hurled stones, iron bars and chairs at each other in the resulting fracas, and seven Ethiopian Orthodox monks and four Egyptian Coptic monks were hospitalised as a result.

This tragi-comic incident is just a small example of the wider battle raging within and over Jerusalem, one that is not only religious, but deeply political. While this Easter passed without incident at the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, the Palestinian struggle for East Jerusalem as a Palestinian city is being severely undermined day by day.

The building of Israel’s Apartheid Wall is isolating the city from its Palestinian hinterland in Ramallah and Bethlehem, while the construction of thousands of new illegal settlement homes for Jewish Israelis on confiscated Palestinian land are fragmenting Palestinian neighbourhoods and severely impeding their development.

While pilgrims from all over the world come to Jerusalem to pray at its holy sites, local Palestinian worshippers, Christians and Muslims alike, are denied free access to the city and depend on permits arbitrarily granted by the Israeli authorities. While Israel puts on a show of beneficent religious tolerance for the outside world, it quietly enforces a relentless system of Apartheid against Palestinians.

Unholy row threatens Holy Sepulchre

Vodpod videos no longer available.

http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/middle_east/7676332.stm

By Wyre Davies

BBC News, Jerusalem

An unholy row is threatening one of the most sacred places in Christianity – the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem.

The centuries-old site, where many Christians believe Jesus was crucified, is visited by hundreds of thousands of pilgrims and tourists every year.

A recent survey says that part of the complex, a rooftop monastery, is in urgent need of repair, but work is being held up by a long-running dispute between two Christian sects who claim ownership of the site.

Within the main building, dark-robed monks with long beards chant and swing incense as they conduct ceremonies in the many small chapels and shrines.

There has been a church on this site for 1,700 years. Over the centuries it has been destroyed and rebuilt several times – but some parts are very old indeed.

Collapse risk

Various Christian denominations – Greek Orthodox, Armenians, Catholics, among others – have always jealously defended and protected their own particular parts of the site.

Disputes are not uncommon, particularly over who has the authority to carry out repairs.

For example, a wooden ladder has remained on a ledge just above the main entrance since the 19th Century – because no-one can agree who has the right to take it down.

The latest row is potentially much more serious.

The Deir al-Sultan monastery was built on part of the main church roof more than 1,000 years ago.

The modest collection of small rooms has been occupied by monks from the Ethiopian Orthodox Church since 1808.

But a recent engineering report by an Israeli institute found that the monastery and part of the roof were “not in a good condition” and that parts of the structure “could collapse, endangering human life”.

Ownership of the monastery, however, is hotly disputed between the Ethiopians and the Egyptian Coptic Church, and the dispute is holding up much-needed repair work.

From a vantage point overlooking the disputed monastery, I discussed the “situation” with Father Antonias el-Orshalamy, General Secretary to the Coptic Church in Jerusalem.

“The Ethiopians were always there as our guests, but then they wanted to take control,” says Father Antonias – referring to the night in 1970 when Coptic monks were all attending midnight prayers in the main Sepulchre church.

With the help of Israeli police, the locks in the Deir al Sultan monastery were changed and the keys given to the Ethiopians.

Subsequent Israeli court rulings, ordering that control be handed back to the Copts, have effectively been ignored – drawing accusations that Israel has shown political bias in favouring the Ethiopians over the (Egyptian) Copts.

Whatever the political and religious arguments, the Ethiopians remain in control of the ancient monastery and refuse to budge.

They will not entertain any suggestion that the Copts should have any say over repairs to the monastery and rooftop courtyard.

In that vein, no one from the Ethiopian Church would speak to us.

‘Unedifying’

Coptic and Ethiopian monks have come to blows in the past but they are not the only ones who have allowed tensions to boil over.

Fights between monks from different sects in the Sepulchre are not uncommon and passions run high, particularly on important holy days.

Father Jerome Murphy O’Connor is a professor at the Ecole Biblique in Jerusalem.

“The whole spectacle is unedifying and totally un-Christian in nature”, says the affable Irish priest, who has witnessed all sorts of church disagreements during his 40 years in the city.

“I’m not hopeful – either for peace in the Middle East or for peace in the Holy Sepulchre,” laughs Father O’Connor.

The impact of age and of so many pilgrims visiting the rooftop monastery and the Sepulchre Church is taking its toll.

While the main church is said to be structurally sound, many parts of the roof in particular are in need of extensive repair.

The Israeli government says it will pay for the work to be carried out if the Copts and Ethiopians can resolve their differences. But after decades of hostility neither side is rushing to compromise.

Africa in Jerusalem – The Ethiopian Church

There can be few monasteries as strange as Deir es-Sultan, home of the Ethiopian Orthodox Church in the Old City of Jerusalem. To come across it without warning is an unusual experience. One walks up a flight of steps behind the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, through a gateway in an old stone wall, and suddenly a tiny African village is revealed: a group of low mud huts huddled together from which comes the clatter of cooking pots. From the middle of a courtyard rises a small and elegant dome. Two priests sit idly chatting on a stone bench. It takes a little time to realize that this is the roof of the Holy Sepulchre itself and that the dome is giving light to the chapel of Saint Helena below, one of the most ancient parts of the complex which make up the most sacred of Christian sites in Jerusalem.

Around the sides of the courtyard are old and shattered walls and in their interstices grow some of those brave and courageous plants which find lodging in the most inhospitable terrain. The Ethiopian church in Jerusalem itself resembles a plant which in Jerusalem has found poor soil but has continued to grow in defiance of the laws of probability and to survive the hardest of winters and the hottest of summers.

Leading off the courtyard is a small chapel where the monks worship. The chapel is dedicated to Saint Michael the Archangel. It is not an impressive structure. A small oblong building, it is capable of seating about 70, with room for a further 40-50 to stand packed together at the times of the great festivals. Below it is another small chapel which also belongs to the Ethiopians, dedicated to “the four living creatures,” in reference to Ezekiel where the prophet beholds four living creatures, one of which has four faces and all of them four wings. The very naming of the chapels is an indication of the deep affinity that the Ethiopian Church feels for the Bible and for Jerusalem.

Another indication of this is given by pictures round the walls of the chapel of St. Michael. They are only about 100 years old, but are in that very distinctive and, to an outsider, exotic style which is peculiarly Ethiopian. The faces of those illustrated are all shown frontally and the eyes in particular stare out with a strange innocence. Their pupils are painted black and are large and lustrous. The largest picture in the chapel shows King Solomon receiving the Queen of Sheba. Around him stand dignitaries while the queen arrives with a large and heavily loaded camel in her train. Among those close to Solomon are two incongruous figures clad in the black costume of Hassidic Jews, a costume which though still to be seen in Jerusalem today, originated in the Europe of the 17th century and would have caused some surprise at the court of Solomon. Who are the Ethiopian Christians who live in this strange environment? Why have they chosen to build on the roof rather than find space in the Holy Sepulchre itself like most of the other ancient Christian churches? The Greeks, the Armenians, the Catholics have secured large portions of the holy site and the Ethiopian Church is only a little less ancient than these. The answer lies in the fact that the Ethiopian Church, though ancient, has always been politically weak, receiving help from Ethiopia itself only at certain periods and in limited measure. Its representatives in Jerusalem were not able to establish a claim to part of the church proper and had to make do with the roof.

According to tradition, the Ethiopians were converted to Christianity in the fourth and fifth centuries by monks, some of whom came from Egypt and some from Syria. These first missionaries found the way prepared for them by the fact that there had been ancient contacts between the Holy Land and Ethiopia. The existence of the ancient Jewish community of Ethiopia is another indication of these contacts. So too is the fact that in the Ethiopian Church there are many features which are peculiarly close to the traditions of Judaism and which are not found elsewhere in Christianity. For example, the Ethiopian Church still practices the circumcision of males after eight days; Saturday in the Ethiopian tradition is a second holy day little less important than Sunday; and in the churches of the Ethiopians the Ark of the Lord features largely. Again the tradition of dancing which is important to Ethiopian ritual and liturgy seems to owe its inspiration at least in part to the dance of David before the Ark.

Most famous of these ancient traditions is of course the visit of the Queen of Sheba to Solomon. Though in the Book of Kings itself, Sheba is not specifically equated with the queen of Ethiopia, no Ethiopian Christian doubts that she came from his country. “And when the Queen of Sheba heard of the fame of Solomon concerning the name of the Lord, she came to prove him with hard questions. And she came to Jerusalem with a very great train, with camels that bear spices, and very much gold, and precious stones: and when she was come to Solomon she communed with him of all that was in her heart.” (I Kings 10:13).

The picture that is seen in the Chapel of St. Michael is only one of many tens of thousands of illustrations of the famous visit to be found in Ethiopian churches and homes everywhere. Tradition in the Ethiopian Church has it that Sheba returned home pregnant and that her son Menelik I, the legendary first emperor of Ethiopia, was her son by Solomon. It is said that Menelik travelled to Jerusalem as a young man to learn more of the wisdom of Solomon and take it back to his own country.

It was perhaps because they found a knowledge of Jerusalem and Jews already existed in Ethiopia that when the Christian missionaries came to the highlands of Ethiopia they were able to speak to the people more easily. In any event, however it may have been, the Christian faith rapidly spread in Ethiopia and according to St. Jerome, by the end of the fourth century Ethiopians were already making pilgrimages to Jerusalem. In the year 636 ce the Caliph Omar, who had entered Jerusalem as a conqueror, issued a firman which set out the rights of Christians in Jerusalem, among them the rights of the Ethiopian Church.

However, little is known of any contacts between the Ethiopian Church and the Holy Land from this early period until the Middle Ages. The Ethiopians themselves believe that a community survived in Jerusalem and that it was supported by funds donated by pilgrims and by occasional gifts from Ethiopian emperors.

There is also little reason to doubt that even at this early stage those contacts were difficult to maintain. The survival of the Ethiopian Church in its home in Africa itself was not easy. On all sides it was surrounded by hostile forces. While the pagans of the interior of Africa certainly had no use for Christianity, a more tangible threat came from the conversion of the peoples of the Sudan and the Horn of Africa to Islam. The fortunes of the Church and of the state of Ethiopia were closely linked and when successive monarchs assumed the throne and fought against their enemies with vigour all was well, but when, as happened on several occasions, the Moslems gained the upper hand, the future of the Church looked bleak. These fluctuations affected the Ethiopians in Jerusalem and continue to affect them up to the present day. They depend upon contacts with Ethiopia and when those contacts are interrupted their economic and political position declines.

However, the very fact that the Church had to struggle to survive both in Ethiopia and in the Holy Land gave it strength, the strength of faith. Also in its favour was the fact that it was not highly centralized. The Ethiopian Church in Ethiopia itself was led by an abuna, or bishop, sent from Egypt to be its leader. This was an ancient tradition dating right back to the very establishment of the church. The abuna, however, had but limited power. Very often he did not know the language of the country to which he was sent and his relations with the local clergy were poor, especially if he tried to enforce discipline on them. For their part, the Christians of Ethiopia centered their tradition on the ancient monasteries and the holy places they established high up in the mountains. These monasteries were the homes of tradition, of culture and of scholarship. In them lived the saints and holy men who played so large a part in Ethiopian religious life. They practiced austerities in the tradition of the Egyptian Church and its monks, and the places where they lived became centres of pilgrimage. They seem to have somewhat resembled the gurus of India today in that they could attract people regardless of where they lived and indifferent to ecclesiastical hierarchy, simply by the way in which they impressed the faithful.

The fact that the church depended upon the individual sanctity of holy men for much of its strength gave it resilience. It is very likely that in Jerusalem too, the experience of struggle and persecution in Ethiopia itself was put to good use by abbots and monks determined to survive despite the circumstances.

Jerusalem bulked large in the eyes of the Ethiopians. In Ethiopia itself, surrounded as it was on all sides by enemies, they could find no community of values with most of their non-Christian neighbours and seldom sought contact with them; the sole exception was the relations with the Coptic Church of Egypt and even these soured after 1700. It was natural, therefore, that in 1937, when Emperor Haile Selassie, one of whose formal titles was “Lion of Judah,” fled from the invading Italians, he made his way first to Jerusalem where he remained until restored to his throne by the British in 1941. Jerusalem was one of the few windows on the world which the Ethiopians enjoyed throughout the centuries.

The Ethiopian Christians resident in Jerusalem often appear in written accounts by mediaeval pilgrims. Writers such as the Dominican Friar Burcardus de Monte Sion in 1283 refer to the piety of the Ethiopians and to their customs. In 1347, Father Nicolo da Pogibonsy, a Franciscan friar from France, who visited the Holy Land that year describes the Ethiopians praying in a chapel called “St. Mary in Golgotha” in the Holy Sepulchre. It is at this time too that the Ethiopian Church in Jerusalem makes a brief appearance on the wider stage. In the year 1438, an Ethiopian delegation attended the Council of Florence which was designed to recreate the unity of Christianity primarily by getting the Greek Orthodox and Catholic Churches together. The Ethiopians were represented by the abbot of the Church from Jerusalem. His embassy attracted considerable curiosity although there appeared to have been no practical results as a result of his participation.

In the 16th century matters took a turn for the worse. The Ethiopian Kingdom was under attack from Ahmad Gran, the ruler of Harar, a Moslem principality east of Ethiopia, and was almost destroyed. Churches were burned, Christians persecuted and forcibly converted, and the emperor compelled to flee. In these circumstances no one had much time to think about Jerusalem, and the community languished. Through poverty they lost their foothold in the main building of the Holy Sepulchre and were finally forced on to the roof, where they remain to this day.

But even there the Ethiopians were not safe. The more powerful churches which enjoyed active support from the rulers of their faith slowly began to encroach upon the Ethiopian properties. Many such properties which had been noted as belonging to the Ethiopians in earlier times are now no longer in their possession.

The Ethiopians somehow managed to hold out, though there are many references to their poverty and the fact that they depended on charity from the Armenians and others for their survival. Writing in the 19th century, an Anglican missionary, William Jarret, notes that some Ethiopian monks joined the Greek Orthodox Church simply to get food.

One group which was particularly antagonistic to the Ethiopians was, surprisingly, the Coptic Church of Egypt. Though the Coptic and Ethiopian Churches were closely allied in terms of theology and organization, the Copts resented the fact that the Ethiopians had broken away from them in the 18th century. When the fortunes of the Ethiopians were at a very low ebb in the early 19th century, the Copts began to harass them.

The ownership of the rooftop monastery of Deir es-Sultan was challenged by the Copts who claimed that it belonged to them. In the year 1838 when plague struck Jerusalem and all the Ethiopian monks died, the Copts took over the monastery and, according to the Ethiopians, burned the library containing the documents which validated the Ethiopian claim to Deir es-Sultan.

With their library burnt and their monks dead the Ethiopians might well have been expected to disappear from Jerusalem. They were saved by a curious combination of circumstances. Of course the emperor and Church in Ethiopia wanted to maintain links with Jerusalem and a foothold in the Holy Land but they might not have been able to do so had it not been for the fact that their aspirations were supported by the British. The Anglican bishop of Jerusalem, Bishop Gobat, had served as a missionary in Ethiopia and had an ambition to convert the Ethiopian Church to Anglicanism, an idea which seems somewhat surprising today. As a mass of correspondence between the British consul and the Foreign Office in London attests, he extended support to the Ethiopians and fought for their rights.

The bitter fight between the Ethiopian Church and the Coptic Church has continued to the present day. When, with British support, the Ethiopians were able to recover the Deir es-Sultan monastery, the keys to the place were left in the hands of the Copts. Confusion and dispute over who owned what went on without interruption. As late as the 1960s, the Jordanian government attempted to intervene in the dispute after there had been a serious fracas over the use of part of the building. Today there is an as yet unresolved case before the Israeli High Court.

The Ethiopians have, of course, no doubt as to their rights and have produced a series of documents on the subject, the latest of which was presented to the Israeli delegation to the Israeli-Egyptian Normalization Talks at the Ethiopian Church in Jerusalem in September, 1986.

In the latter half of the 19th century, the position of the Church in the Holy Land began to improve. This was largely because in Ethiopia itself a series of strong monarchs had come to power who began to unite the various provinces under one centralized administration. The Emperor Yohanes came to the throne and began to assert himself to improve Ethiopia’s position on a wider stage. He was fortunate that in Jerusalem at that time the leader of the community was one of the few Ethiopian individuals known to history by more than his name. He was Abbawalda Sama’et Walda Yohanes, a man of energy and vigour. In the year 1888, the community bought a plot of land outside the walls of Jerusalem with treasure which Emperor Yohanes had captured from the Turks; some said he had captured three boxes of treasure, some seven, but however much it was, it was enough to buy the land and begin construction of a new monastery and church. This complex is called Debre Gannet which means the “Monastery of Paradise” in Amharic. It is situated off Prophets’ Street in Jerusalem and gave its name to Ethiopia Street on which it stands.

Once the decision to build a new church was taken, the whole position of the Ethiopians began to change for the better. The community grew larger until some 40-50 monks and a smaller number of nuns were in residence by 1900, a number which it has maintained up until today. Many of the nuns were widows of priests (for priests in the Ethiopian church are not celibate) or members of aristocratic families who came to Jerusalem in pious retirement to houses which they built and lived in, and, on their death, donated to the community. The Israel Broadcasting Authority building in Jerusalem is housed in a building belonging to the Ethiopian Church for which rent is paid.

The “new” church – Debre Gannet – is an impressive building built on a circular pattern used in most of the principal churches of Ethiopia. It is entered through a large door and stands in a quiet and secluded courtyard. Once inside, the worshipper is aware of its very considerable height. There is no nave as in most western churches but rather a great circular corridor which surrounds the central Ark and which is made attractive to the worshipper as well as to the seeker after aesthetic pleasure, by the presence of a variety of pictures dating back some hundred years or so, most showing saints of the church.

Debre Gannet now shares with Deir es-Sultan the role of providing a home for the monastic community of Ethiopians in the Holy Land. During the last hundred years they have also acquired properties in Bethany, Jericho and on the river Jordan.

The fortunes of the Church would thus appear to have improved, but there are still difficulties. Many of these have been caused over the last 50 years by political turmoil in Ethiopia itself. In 1936, when the Italians conquered Ethiopia, some of the monks recognized the Italian rule in their country while others refused. The struggle between the two parties resolved in favour of the Ethiopian nationalists in 1941 when the Italians were defeated. The monks who had supported the Italians were driven out of the Jerusalem monastery and reduced to utter penury from which they were only relieved by a grudging pension paid by the British mandatory authorities.

The overthrow of the Emperor Haile Selassie by the communists in 1973 was another cause for turmoil. Some monks who were loyal to the imperial regime were no longer able to remain in the monastery while the community itself was augmented by a number of individuals, not all of them monks, who had left Ethiopia for political reasons. Today the community of monks and nuns has been augmented by a sizable group of lay people. There was a variety of internal conflicts which arose as a direct result of antagonism between those who had felt at home only with the government of the Emperor and with the traditional social order and those who were prepared to compromise with change. In this the community in Jerusalem only reflected the wider concerns of the Church in Ethiopia itself. The recent defeat of the communist regime in Ethiopia and the establishment of an Ethiopian embassy in Israel have, however, improved matters so far as the community in Jerusalem is concerned.

For more than 1500 years, the Church of Ethiopia has survived in Jerusalem. Its survival has not, in the last resort, been dependent on politics, but on the faith of individual monks and it is to the lives of these monks that we should look for the vindication of the Church’s presence in Jerusalem.

The Ethiopian monks of today, whether in Jerusalem or in Ethiopia itself, are supported by revenues from church lands and properties and gifts of the faithful. The monks are far from rich. They are attracted to Jerusalem not by a hope for material gain or comfort, but by faith.

It has been a feature of the Ethiopian Church in Jerusalem that its members, who are Amharic-speaking, seldom became fluent in the tongues of the country in which they live. Even today many monks speak neither Arabic nor Hebrew, nor indeed any other language, and are entirely dependent for their contact with the outside world on those of the community who do. Most of them are men of simple piety brought to Jerusalem by the belief that it is the most holy of Holy Places. The life they lead is highly structured. Meals are eaten in common and their whole life revolves around prayer services and great feasts. The monks take part in services held twice a day between four and six a.m. and between four and five p.m. On the days immediately preceding Easter as well as the Feast of Our Lady, in August, the morning service lasts from two to six a.m. On other saints’ days, the qudase, or Mass, is celebrated.

The services involve long periods of standing and it is for this reason that a feature of the church is the long sticks with carved chin rests which the monks use for support. Similar sticks, incidentally, are used by shepherds in Ethiopia as they watch their flocks.

On the occasion of the important feasts, dancing and making music with traditional instruments play a very large part. By far the most important are the series of celebrations surrounding Easter. In 1502, a German pilgrim Bernhard von Breidenbach, wrote “with zeal do the people gather for the celebration of Mass. Especially on the Feasts, and then both men and women begin to rejoice and to dance, to clap their hands and to form circles, here six or seven, there nine or ten, and sometimes they keep singing like that all the night, particularly on the night of the Resurrection of our Lord, where they do not stop singing till dawn and sometimes they do this so fervently that they become completely exhausted.”

Perhaps the most memorable of the Easter activities is Palm Sunday. For this celebration of the entry of Christ to Jerusalem, not only monks but all the lay members of the 300 or so Ethiopian community in Jerusalem gather in the courtyard of Deir es-Sultan. All over Jerusalem other Christians are also celebrating Palm Sunday but none do so in a more heartfelt way than the Ethiopians, who act out the events of Easter week in a style all their own.

The service begins at midnight in the Chapel of St. Michael in Deir es-Sultan, and lasts until eight a.m. Of this, six hours is a special commemorative service and the remaining two celebrate the Mass. It is not only monks who have stomach for so long a service. At the back of the church stand women, in traditional cotton dresses and shawls of white. The faces of the congregation are remarkable for their concentration. At about half-past eight at the end of the service, everybody leaves the chapel and comes out on the roof looking cheerful and not in the least tired. The archbishop and his fellow priests go into a large tent nearby where they prepare themselves for the solemn procession.

There they begin their prayers chanting “I rejoiced when they said unto thee Let us go unto the House of the Lord’. Our feet shall stand within thy gates; Jerusalem is builded as a city.” At the end of the service palm branches are brought to the archbishop who blesses them and distributes them to the congregation and to the monks. The whole crowd walks in procession round the courtyard. For outsiders, part of the interest in these celebrations is in the exoticism: the elaborate ecclesiastical garments of the priests and especially the archbishop and his senior colleagues; the decorated and tasseled umbrellas in velvet and gold which are held over the heads of notables, the music itself and the presence among the crowd of a few itinerant musicians playing on small stringed instruments and singing spontaneous hymns of praise to the crowd. For the monks the ceremony has a different meaning – it is the high point of the year, the ultimate celebration of their faith.

When they are not taking part in feasts or fasts (there are a great number of fasts in the Ethiopian rite), the monks and nuns make use of their time for their own spiritual practice. Private prayers are a very important part of the monastic life of the Ethiopian church. Their characteristic method is the repetition of certain sacred texts. The Psalms of David are particularly appreciated, as is the Gospel of St. John.

However, the Ethiopian monks must also contribute to the communal life of the monastery. They are bound by a rule which is perhaps less strict than that of some Western monks but still demands of them celibacy, the avoidance of sin, and obedience to the abbot. They are also expected to look after themselves insofar as they must garden, clean and paint their houses and share in the life of the community. However, they do not live in communal dwellings as do monks in the Catholic tradition. They are also given considerable latitude in their choice of activities. Some have taken up painting and woodcarving while others prefer to spend their time in study; one or two have withdrawn from the world and become solitary hermits. The most famous of these, who died in the early eighties, was a monk who did not speak for 30 years but who, if appealed to by an individual, would give his guidance in writing. This man, who acquired a reputation for sanctity, was buried as a saint.

As for the lay community of devout individuals and, on occasion, political exiles, it is more closely involved with society outside the monasteries than are the monks and nuns. Members of the Ethiopian community work as nursing sisters in hospitals and the young people study in the Anglican School, an international school in Jerusalem, or in regular Israeli schools.

In recent years, the pilgrimage to Jerusalem from Ethiopia has attracted more and more people. In 1993, some 450 pilgrims flew to Jerusalem at Easter. Looking after them provides a source of income for the local community. However, the community as a whole is still a poor one and has a constant struggle to preserve its identity. A small school maintained with care and affection provides instruction in Amharic and in the traditions of the Ethiopian community and Church in Ethiopia but it only functions at weekends.

The arrival of some 30,000 Jews from Ethiopia during the last few years has, to some extent, served to diminish the sense of isolation of the Ethiopian Christian community but it has not much affected its day-to-day life.

The monks of the Ethiopian Church live, as it were, on an island where their lives change very slowly – an island to which they have been drawn through faith and where they have found a degree of contentment. Asked why he had come to Jerusalem, one elderly monk at first seemed to fail to grasp the question. Then he burst out “because it is Jerusalem” – an answer he felt quite sufficient, as indeed it is.